Amar, Akhil Reed, The Bill of Rights: Creation and Reconstruction (New Haven & London: Yale U. Press, 1998).

Bernstein, David E., Only One Place of Redress: African Americans, Labor Regulations, and the Courts From Reconstruction to the New Deal (Durham & London: Duke U. Press, 2001) ("This book presents several case studies of how facially neutral occupational regulations passed between the 1870s and the 1930s harmed African American workers. Sometimes racism motivated the laws, either directly (as when the sponsors of the legislation were themselves racists) or indirectly (when legislative sponsors responded to racism among their constituents). Some laws had the primary goal of restricting African American access to the labor force, whereas in other instances this was a secondary goal related to the broader goal of limiting competition faced by entrenched workers. In yet other situations, racism did not motivate the laws, but the adverse effects on African Americans were foreseen, and critics pointed out the likely adverse effects when the legislation was under consideration. And finally, whether intended or not, whether actually foreseen or not, the adverse effects of some legislation were foreseeable in light of the way labor markets operate." Id. at 5.).

Brinkley, Douglas, The Quiet World: Saving Alaska's Wilderness Kingdom, 1879- 1960 (New York: Harper, 2011).

Cohen, Andrew Wender, The Racketeer's Progress: Chicago and the Struggle for the Modern American Economy, 1900-1940 (Cambridge: Cambridge U. Press, 2004).

Culver, John C. & John Hyde, American Dreamer A Life of Henry A. Wallace (New York: Norton, 2000) ("Wallace gave the star-studded crowd what it wanted. 'Today an ugly fear is spread across America--the fear of communism,' he declared. 'I say those who fear communism lack faith in democracy. I am not afraid of communism.'" "In blistering language Wallace threw open the door to a closet containing America's darkest moments: 'We burned innocent women on charge of witchcraft. We earned the scorn of the world for lynching negroes. We hounded labor leaders and socialists at the turn of the century. We drove 100,000 innocent men and women from their homes in California because they were of Japanese ancestry. . . . We branded ourselves forever in the eyes of the world for the murder by state of two humble and glorious immigrants--Sacco and Vanzetti. . . . These acts today fill us with burning shame. Now other men seek to fasten new shame on America. . . . I mean the group of bigots first known as the Dies Committee, then the Rankin Committee, now the Thomas Committee--three names for fascists the world over to roll on their tongues with pride.'" Id. at 445 (citing Henry A. Wallace, text of Los Angels speech, May 19, 1947.).

Cohen, Andrew Wender, The Racketeer's Progress: Chicago and the Struggle for the Modern American Economy, 1900-1940 (Cambridge: Cambridge U. Press, 2004).

Culver, John C. & John Hyde, American Dreamer A Life of Henry A. Wallace (New York: Norton, 2000) ("Wallace gave the star-studded crowd what it wanted. 'Today an ugly fear is spread across America--the fear of communism,' he declared. 'I say those who fear communism lack faith in democracy. I am not afraid of communism.'" "In blistering language Wallace threw open the door to a closet containing America's darkest moments: 'We burned innocent women on charge of witchcraft. We earned the scorn of the world for lynching negroes. We hounded labor leaders and socialists at the turn of the century. We drove 100,000 innocent men and women from their homes in California because they were of Japanese ancestry. . . . We branded ourselves forever in the eyes of the world for the murder by state of two humble and glorious immigrants--Sacco and Vanzetti. . . . These acts today fill us with burning shame. Now other men seek to fasten new shame on America. . . . I mean the group of bigots first known as the Dies Committee, then the Rankin Committee, now the Thomas Committee--three names for fascists the world over to roll on their tongues with pride.'" Id. at 445 (citing Henry A. Wallace, text of Los Angels speech, May 19, 1947.).

Duberman, Martin, A Saving Remnant: The Radical Lives of Barbara Deming and David McReynolds (New York & London: The New Press, 2011) ("The phrase 'a saving remnant' has historically referred to that small number of people neither indoctrinated nor frightened into accepting oppressive social conditions. Unlike the general populace, they openly challenge the reigning powers=that-be and speak out early and passionately against injustice of various kinds. They attempt, with uneven degrees of success, to awaken and mobilize others to join in the struggle for a more benevolent, egalitarian society." Id. at xi.).

Dunn, Susan, Roosevelt's Purge: How FDR Fought to Change the Democratic Party (Cambridge, Massachusetts, & London, England: Belknap/Harvard U. Press, 2010) ("But the purge represented even more than a scheme to restart the New Deal. It was also the precursor of a historic transformation of American political parties. In the aftermath of the purge, the momentum for the kind of party realignment Roosevelt had sought in 1938 through the eviction of the Democratic Party's conservative wing would gather steam, first with the 'Dixiecrat' rebellion of conservative southern Democrats in 1948 and then, over the decades that followed, with Lyndon Johnson's Civil Rights Acts and then with Goldwater, Nixon, and Reagan's appeal to right-leaning Democrats to join the Republicans. By the end of the century, the irreconcilable tensions with the Democratic Party had exploded, transforming the nation's tradition political landscape--and the once solidly Democratic South was solid not more." Roosevelt's purge was a valiant if premature and mismanaged plan to remedy a complex political dilemma. . . . But the legacy of the purge colors American politics to this day." Id. at 7.).

Ellis, Joseph J., First Family: Abigail and John Adams (New York: Knopf, 2010).

Dunn, Susan, Roosevelt's Purge: How FDR Fought to Change the Democratic Party (Cambridge, Massachusetts, & London, England: Belknap/Harvard U. Press, 2010) ("But the purge represented even more than a scheme to restart the New Deal. It was also the precursor of a historic transformation of American political parties. In the aftermath of the purge, the momentum for the kind of party realignment Roosevelt had sought in 1938 through the eviction of the Democratic Party's conservative wing would gather steam, first with the 'Dixiecrat' rebellion of conservative southern Democrats in 1948 and then, over the decades that followed, with Lyndon Johnson's Civil Rights Acts and then with Goldwater, Nixon, and Reagan's appeal to right-leaning Democrats to join the Republicans. By the end of the century, the irreconcilable tensions with the Democratic Party had exploded, transforming the nation's tradition political landscape--and the once solidly Democratic South was solid not more." Roosevelt's purge was a valiant if premature and mismanaged plan to remedy a complex political dilemma. . . . But the legacy of the purge colors American politics to this day." Id. at 7.).

Ellis, Joseph J., First Family: Abigail and John Adams (New York: Knopf, 2010).

Feldman, Noah, Scorpions: The Battles and Triumphs of FDR's Great Supreme Court Justices (New York: Twelve, 2010) (Felix Frankfurter, Hugo L. Black, William O. Douglas, and Robert H. Jackson).

Forbath, William E., Law and the Shaping of the American Labor Movement (Cambridge, Massachusetts, & London, England: Harvard U. Press, 1989, 1991) ("America's labor laws provide far fewer protections against exploitation, injury, illness, and unemployment than the laws of the dozen other leading Western industrial nations. Our laws also exclude more workers from their crabbed coverage. A key reason for the paltriness of American labor law and social provision lies in the fact that American workers never forged a class-based political movement to press for more generous and inclusive protections. Elsewhere in the decades around the turn of the century, labor's national organizations embraced broad, class-based programs of reform and redistribution, but the American Federation of Labor spurned them . . . . How does one explain this; how account for organized labor's historical devotion to voluntarism? And what part did the legal order itself play in the story?" Id. at 1. "'Voluntarism' is the political philosophy that predominated in the American labor movement from the 1890s through the 1920s and continues to color organized labor's outlook today. It stands for a staunch commitment to the 'private' ordering of industrial relations between unions and employers. Voluntarism teaches that workers should pursue improvements in their living and working conditions through collective bargaining and concerted action in the private sphere rather than through public political action and legislation. This voluntarism is labor's version of laissez-faire, and anti-statist philosophy that says the 'best thing the State can do for labor is to leave Labor alone (Id. at 1-2, fn. 3, quoting Gompers, "Judicial Vindication of Labor's Claims," 7 Am. Federationist 283, 284 (1901).).

Forbath, William E., Law and the Shaping of the American Labor Movement (Cambridge, Massachusetts, & London, England: Harvard U. Press, 1989, 1991) ("America's labor laws provide far fewer protections against exploitation, injury, illness, and unemployment than the laws of the dozen other leading Western industrial nations. Our laws also exclude more workers from their crabbed coverage. A key reason for the paltriness of American labor law and social provision lies in the fact that American workers never forged a class-based political movement to press for more generous and inclusive protections. Elsewhere in the decades around the turn of the century, labor's national organizations embraced broad, class-based programs of reform and redistribution, but the American Federation of Labor spurned them . . . . How does one explain this; how account for organized labor's historical devotion to voluntarism? And what part did the legal order itself play in the story?" Id. at 1. "'Voluntarism' is the political philosophy that predominated in the American labor movement from the 1890s through the 1920s and continues to color organized labor's outlook today. It stands for a staunch commitment to the 'private' ordering of industrial relations between unions and employers. Voluntarism teaches that workers should pursue improvements in their living and working conditions through collective bargaining and concerted action in the private sphere rather than through public political action and legislation. This voluntarism is labor's version of laissez-faire, and anti-statist philosophy that says the 'best thing the State can do for labor is to leave Labor alone (Id. at 1-2, fn. 3, quoting Gompers, "Judicial Vindication of Labor's Claims," 7 Am. Federationist 283, 284 (1901).).

Heiferman, Ronald Ian, The Cairo Conference of 1943: Roosevelt, Churchill, Chiang Kai-shek and Madame Chiang (Jefferson, North Carolina, & London, England: McFarland, 2011) ("Albeit less studied, the interaction of Churchill, Roosevelt, and Chiang in Cairo is every bit as compelling from a human interest perspective as the interplay between Churchill, Roosevelt, and Stalin at Teheran and Yalta and offers a sobering reminder of what can happen when policy is made at the very highest level by individuals who know relatively little about the culture of their partners and are not able to separate myths and stereotypes from realities. Summit conferences may make for good theater, but do not necessarily result in good policies, as an examination of the Cairo Conference reveals." Id. at 1. "How much of the deadlock over Southeast Asian policy and Chinese politics was due to such rivalry between the president and the prime minister is not entirely clear, but surely the contest of wills between Churchill and Roosevelt was contributing to the impasse at Cairo. It was not merely the menage-a-quatre between Churchill, de Gaulle, Chiang, and Roosevelt that complicated the proceedings in Cairo and Teheran. Egos were also interfering with coming to terms with the hard decisions the Allies had to make." Id. at 147.).

Holt, Thomas C., Children of Fire: A History of African Americans (New York: Hill & Wang, 201o).

Jasanoff, Maya, Liberty's Exiles: American Loyalists in the Revolutionary World (New York: Knopf, 2011) ("There were two sides in the American Revolution--but only one was on display early in the afternoon of November 25, 1783, when General George Washington rode in a grey horse into New York City. . . . Today, the British were going. A cannon shot at 1 p.m. sounded the departure of the last British troops from their posts. . . . The British occupation of the United States was officially over." Id. at 5. "Generations of New Yorkers commemorated November 25 as 'Evacuation Day'--an anniversary that was later folded into the more enduring November celebration of American national togetherness, Thanksgiving Day." "But what if you hadn't wanted the British to leave? Mixed among the happy New York crowd that day were other, less cheerful faces. For loyalists--colonists who had sided with Britain during the war--the departure of the British troops spelled worry, not jubilation. . . . The British withdrawal raised urgent questions about their future. What kind of treatment could they expect in the new United States? Would they be jailed? Would they be attacked? Confronting real doubts about their lives, liberty, and potential happiness in the United States, sixty thousand loyalists decided to follow the British and take their chances elsewhere in the British Empire. They took fifteen thousand black slaves with them, bringing the total exodus to seventy-five thousand people--or about one in forty members of the American population." "They traveled to Canada, they sailed for Britain, they journeyed to the Bahamas and the West Indies; some would venture still farther afield, to Africa and India. But wherever they went, this voyage into exile was a trip into the unknown, In America the refugees left behind friends and relatives, careers and land, houses and native streets--the entire milieu in which they had built their lives. For them, American seemed less 'an Assylum to the persecuted' that a potential persecutor. It was the British Empire that would be their asylum, offering land, emergency relief, and financial incentives to help them start over. Evacuation Day did not mark an end for the loyalist refugees. It was the fresh beginning--and it carried them into a dynamic if uncertain new world." Id. at 6.).

Kluger, Richard, The Bitter Waters of Medicine Greek: A Tragic Clash Between White and Native America (New York:Knopf, 2011) ("The governor may have felt that the impact from the drastic reduction in tribal living space he proposed at Medicine Creek would be cushioned to some degree by Article 3 of the treaty. This article, Gibbs's brainstorm, allowed the signatory tribes to continue to 'take fish at all usual and accustomed grounds and stations . . . in common with all citizens of the territory' as well as to enjoy 'the privilege of hunting, gathering roots and berries, and pasturing their horses on open and unclaimed lands.' Even though the Indians' residential space was to be narrowly confined, they were free to move about as they had always done for the purpose of feeding themselves and caring for their livestock. Stevens might have hoped this liberating expedient would also serve to relieve the territorial and federal governments of the economic burden of saving the Indians from starvation." "Upon closer parsing of Gibbs's legalese, however, the innocent-sounding conditional phrase tacked on at the end raises doubts. The Indians were free to leave the reservations for food-gathering and pasturing their animals as before--but only 'on open and unclaimed lands.' Weren't the shortly expected multitudes of new white settlers going to file claims to whatever open lands remained in the region. Wasn't such a prize precisely why they were moving to Washington Territory and why the treaties were being drawn up--to get the Indians off their lands so that Americans could take their place? 'Open and unclaimed lands' for tribal fishing, hunting and pasturage would become a sharply diminishing commodity with each passing year unless the government were to set aside public fishing and hunting areas permanently closed to white settlements. No such provision was mentioned in the treaty, so as a practical matter, exile of the Nisquallies to a barren and remote bluff along the Sound would cut them off from their normal, easy sources of nourishment, distance them from work sites where they could earn the white man 's welcome wages, and generally hasten the prospect of their decline." Id. at 86-87. "To further justify himself, Steven told Manypenny that because the treaty's Article 6 allowed the President to move or consolidate reservation sites whenever it suited the U.S. government, the governor planned eventually to move the Medicine Creek Treaty tribes onto a single, consolidated reservation, perhaps as early as that summer of 1855. In other words, Stevens and his staff had not only dispossessed the Indians at Medicine Creek of all but a miserable fraction of their lands but had also deceived them into believing that the three reservations granted to them would provide irreducible havens where they could maintain their tribal identities in perpetuity." Id. at 105-106. From the bookjacket: "The riveting story of a dramatic confrontation between native Americans and white settlers, a compelling conflict that unfolded in the newly created Washington Territory from 1853 to 1857. " When appointed Washington's first governor, Isaac Ingalls Stevens, an ambitious military man turned politician, had one goal: to persuade (peacefully if possible) the Indians of the Puget Sound region to turn over their ancestral lands to the federal government. In return, they were to be consigned to reservations unsuitable for hunting, fishing, or grazing, their traditional means of sustaining life. The result was an outbreak of violence and rebellion, a tragic episode of frontier oppression and injustice." "With . . . empathy and scholarly acuity . . . Kluger recounts the impact of Steven's program on the Nisqually tribe, whose chief, Leschi, sparked the native resistance movement. . .The conflict between these two complicated and driven men [i.e., Stevens and Leschi]--and their supporters--explosively and enormously at odds with each other, was to have echoes into the future." Needless to say, and as one might suspect/expect, this is not the American history taught to schoolchildren in American schools.).

Levinson, Sanford, Written in Stone: Public Monuments in Changing Societies (Durham & London: Duke U. Press, 1998).

McLennan, Rebecca M., The Crisis of Imprisonment: Protest, Politics, and the Making of the American Penal State, 1776-1941 (Cambridge: Cambridge U. Press, 2008) (McLennan argues that "a long continuum of episodic instability, conflict, and political crisis has characterized prison-based punishment in the United States, from the early republican period, down through the nineteenth century, and deep into the twentieth. Far from being the exception to the norm, Sing Sing stood squarely within a long, broad, American tradition of debate, riot, and political and moral crisis over the rights and wrongs of legal punishment, the proper exercise of state power, ad the just deserts of convicted offenders. This book traces the lineage, meaning, and consequences of popular conflicts over legal punishment, from the early republican penitentiary-house, through the great prison factories of the Gilded Age, and the penal-social laboratories of the Progressive Era, to the ambitious, penal state-building programs of the New Deal era." Id. at 3. "Shock punishments administered a swift, maximally painful but typically undebilitating, dose of physical pain to the prisoner's central nervous system. 'Slugging,' stringing-up (or tricing), and ice-bathing were the three most common techniques of the shock mode or punishment and they were routinely meted out to prisoners for poor work or disobedience in the workshops. Such punishments administered short, sharp, bursts of searing pain, and hinted at the physical devastation or death that would follow should the prisoner refuse or fail to render up the required quality and quantity of labor. At Sing Sing, Clinton, Elmira and Albany prisons, a laggardly worker could find himself whisked out of the factory to a punishment room, where a guard locked him to the floor and wall, in a bent-over position, and administered a 'slugging' to his bare buttocks with a wooden or thick leather paddle." Id. at 128-129.).

Ngai, Mae, The Lucky Ones: One Family and the Extraordinary Invention of Chinese America (Boston & New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010) (See Anderson Tepper, "Melting Pot," NYT Book Review, Sunday, 9/19/2010).

Ngai, Mae, The Lucky Ones: One Family and the Extraordinary Invention of Chinese America (Boston & New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010) (See Anderson Tepper, "Melting Pot," NYT Book Review, Sunday, 9/19/2010).

Oshinsky, David M., "Worse Than Slavery: Parchman Farm and the Ordeal of Jim Crow Justice (New York & London: Free Press, 1991) ("Railroad work was dangerous under any circumstances. . . ." "But the convict was more vulnerable than the free worker, and he paid a greater price. Despised, powerless, and expendable, he could be made to do any job, at any pace, in any location. 'Why? Because he is a convict,' a railroad official explained, 'and if he dies it is a small loss, and we can make him work there, while we cannot get free men to do the same kind of labor for, say, six times as much as the convict costs.'" "On many railroads, convicts were moved from job to job in a rolling iron cage, which also provided their lodging at the site. The cage--eight feet wide, fifteen feet long, and eight feet high--housed upwards of twenty men. It was similar 'to those used for circus animals,' wrote a prison official, except it 'did not have the privacy which would be given to a respectable lion, tiger, or bear.'" Id. at 58-59.).

Powers, Thomas, The Killing of Crazy Horse (New York: Knopf, 2010) (See Evan Thomas, "A Good Day to Die," NYT, 11/14/2010; and Ian Frazier, "The Magic of Crazy Horse," New York Review of Books, 2/24/2011, at 32.).

Rasmussen, Daniel, American Uprising: The Untold Story of America's Largest Slave Revolt (New York: Harper, 2011) ("Claiborne put the city into lockdown. 'No male Negro is permitted to pass the streets after 6 o'clock,' he ordered. The city garrison would fire a gun at dusk--the final warning to any black man still in the streets. The gun shot left little to the imagination of what would happen to any male slave found outdoors at night." Id. at 118-119. "Their judicial proceeding complete, the planters shot each of the eighteen slaves sentenced to death, and chopped off their heads and put them on pikes. These pikes they drove into the ground on the levee, 'where every guilty one will undergo the just chastisement for their crimes, with the end of providing a terrible example to all the malefactors who in the future would seek to disrupt the public tranquility.' Kook's and Quamana's heads would be eaten by the crows as the planters returned to their labors." Id. at 157. "If heads on poles were symbols of American authority, they were also symbols of the costs of Americanization. If heads on poles were symbols of control, they were also symbols of the ritual of violence that was the constant underlying element of Louisiana society. This was the world Claiborne and the planter made. This was New Orleans, and the German Coast, in 1811: a land of death; a land of spectacular violence; a land of sugar, slaves, and violent visions." Id. at 163. Also see Adam Goodheart, "Violence and Retribution," NYT Book Review, Sunday, 2/6/2011, at 24. "Rasmussen could d have revisited the Mississippi levees to bring his story of racial paranoia and retribution full circle. In New Orleans in 2005, amid the nightmare of Hurricane Katrina, white panic over alleged rapes and murders by African-Americans led to a still-uncounted number of civilian shootings by police officers and vigilantes. One man was shot in the back while crossing a bridge through a black neighborhood: the Claiborne Avenue overpass." Id.).

Reed, Christopher Robert, Black Chicago's First Century: Volume 1, 1833-1900 (Columbus, Missouri, & London, England: U. of Missouri Press, 2005).

Powers, Thomas, The Killing of Crazy Horse (New York: Knopf, 2010) (See Evan Thomas, "A Good Day to Die," NYT, 11/14/2010; and Ian Frazier, "The Magic of Crazy Horse," New York Review of Books, 2/24/2011, at 32.).

Rasmussen, Daniel, American Uprising: The Untold Story of America's Largest Slave Revolt (New York: Harper, 2011) ("Claiborne put the city into lockdown. 'No male Negro is permitted to pass the streets after 6 o'clock,' he ordered. The city garrison would fire a gun at dusk--the final warning to any black man still in the streets. The gun shot left little to the imagination of what would happen to any male slave found outdoors at night." Id. at 118-119. "Their judicial proceeding complete, the planters shot each of the eighteen slaves sentenced to death, and chopped off their heads and put them on pikes. These pikes they drove into the ground on the levee, 'where every guilty one will undergo the just chastisement for their crimes, with the end of providing a terrible example to all the malefactors who in the future would seek to disrupt the public tranquility.' Kook's and Quamana's heads would be eaten by the crows as the planters returned to their labors." Id. at 157. "If heads on poles were symbols of American authority, they were also symbols of the costs of Americanization. If heads on poles were symbols of control, they were also symbols of the ritual of violence that was the constant underlying element of Louisiana society. This was the world Claiborne and the planter made. This was New Orleans, and the German Coast, in 1811: a land of death; a land of spectacular violence; a land of sugar, slaves, and violent visions." Id. at 163. Also see Adam Goodheart, "Violence and Retribution," NYT Book Review, Sunday, 2/6/2011, at 24. "Rasmussen could d have revisited the Mississippi levees to bring his story of racial paranoia and retribution full circle. In New Orleans in 2005, amid the nightmare of Hurricane Katrina, white panic over alleged rapes and murders by African-Americans led to a still-uncounted number of civilian shootings by police officers and vigilantes. One man was shot in the back while crossing a bridge through a black neighborhood: the Claiborne Avenue overpass." Id.).

Reed, Christopher Robert, Black Chicago's First Century: Volume 1, 1833-1900 (Columbus, Missouri, & London, England: U. of Missouri Press, 2005).

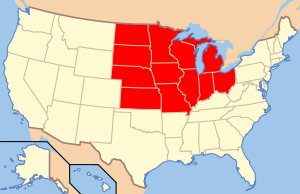

Sharfstein, Daniel J., The Invisible Line: Three American Families and the Secret Journey from Black to White (New York: The Penguin Press, 2011).

Wuthnow, Robert, Remaking the Heartland: Middle America Since the 1950s (Princeton & Oxford: Princeton U. Press, 2011) ("The transformation that occurred in the American Middle West cannot be attributed to any single cause, tempting as it may be to seek answers in the magic of, say, rugged individualism. I break the narrative into several parts. The first is about the struggles of Middle Western farmers in the 1950s. Difficult as those struggles were, they enabled farming to become more efficient and capital intensive. The second is a saga of cultural redefinition. As the Middle West modernized, it rediscovered its legends of hardy pioneers, adventuresome cowboys, and Dust Bowl survivors. It reshaped these legends into a less spatially confined image of congeniality and can-do inventiveness. These new understandings improved the region's self image and contributed to its ability to transform itself. A third story is about public education. The region invested heavily in schools, administered them well, and encouraged children to regard school achievement as their best hope for occupational success. Higher education became the source of both upward and outward mobility. A fourth story tells of small communities that are dying by the hundreds and yet are not doing so very quickly or completely. Community downsizing has been a matter of great concern to the residents of these communities, but it has worked remarkably well for the region as a whole. Small communities remain attractive for low-income families needing inexpensive housing. Many of these communities are within commuting distance of larger towns where work can be found in construction, manufacturing, and human services. High fuel prices are making it harder for these commuters, but electronic technology and decentralization are opening new opportunities. A fifth story examines the growth of large-scale agribusiness and its effects on the ethnic composition of the region. Contrary to takes about ethnic conflicts, the picture that comes into focus from closer inspection is one of greater diversity over a longer period, continuing difficulties for immigrants and undocumented workers, and yet shows a striking degree of communitywide accommodation to new realities, A final story is about the phenomenon least expected in this part of the county--rapidly expanding edge cities. The growth of these communities has been nothing short of spectacular. A yet the sources of this growth lie in more than simply the availibility of land and the decline of smaller towns." Id. at x-xi. Readers should not confuse Wuthnow's "Middle West" with the much larger Midwest. The former is comprised of "Iowa, Kansas, Nebraska, Minnesota, Missouri, North and South Dakota, Arkansas, and Oklahoma." Id. at 1. Of course, I was rather shocked to find that , being an Illinoi[s]an, I not consider to be from the Mid[dle] West. Fortunately, the good people at and the United States Census Bureau and Wikipedia (see below citations and footnotes omitted) have stopped my heart from pounding. Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, Wisconsin are in, while Arkansas and Oklahoma are out. Let's us be real. No one ever thinks of Oklahoma and Arkansas as being part of 'the heartbeat of America.').

"The Midwestern United States (in the U.S. generally referred to as the Midwest) is one of the four geographic regions within the United States of America used by the United States Census Bureau in its reporting.

"The region consists of 12 states in the north-central United States: States: Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota and Wisconsin. A 2006 Census Bureau estimate put the population at 66,217,736. Both the geographic center of the contiguous U.S. and the population center of the U.S. are in the Midwest. The United States Census Bureau divides this region into the East North Central States (essentially the Great Lakes States) and the West North Central States. Chicago is the largest city in the region, followed by Indianapolis, Columbus, Detroit, and Milwaukee. The Chicago-Joliet-Naperville, IL- IN-WI MSA is the largest metropolitan statistical area, followed by the Detroit-Warren-Livonia, MI MSA, the Minneapolis-St. Paul--Bloomington, MNpWI MSA, and the Greater St. Louis area. Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan is the oldest city in the region, having been founded by French missionaries and explorers in 1668.

"The term Midwest has been in common use for over 100 years. A variant term, "Middle West", has been in use since the 19th century and remains relatively common.[3] Another term sometimes applied to the same general region is "the heartland".[4] Other designations for the region have fallen into disuse, such as the "Northwest" or "Old Northwest" (from "Northwest Territory") and "Mid-America". Since the book Middletown appeared in 1929, sociologists have often used Midwestern cities (and the Midwest generally) as "typical" of the entire nation.[5] The region has a higher employment-to-population ratio (the percentage of employed people at least 16 years old) than the Northeast, the West, the South, or the Sun Belt states.[6]"